Radio

A little over a month ago, I posted on my Tumblr about building a cheap Arduino clone (which is stretching the term to mean running the Arduino bootloader on a bare ATmega) for some radio experiments.

Hello World

I got “Hello, World” working (or, I got “68656c6c6f” working, really) with full-size Arduino and Boarduino boards. The VirtualWire library makes this really simple (though the library is now deprecated in favour of RadioHead).

We even had a little fun in the office hooking up a DHT11 temperature sensor and a batch of LEDs repurposed as ‘light level detectors’ and feeding those into the big graphing stack we use.

Jealousy

This tied up a FTDI RS232 cable and was highly inelegant. I saw Dickson Chow’s Plant Friends and was instantly jealous. I wanted to make something as tidy as that.

Using a Raspberry Pi to receive the VirtualWire protocol is difficult – the Arduino only has one thing to do and you can easily register your own interrupt handler (which is what VirtualWire does) – so timing sensitive protocols aren’t (much of) a problem. These exact things are a problem when you’re running a multi-tasking operating system, like Linux.

I poured a little time into this: lots of tight loops in C, and time spent debugging floating inputs and problems with running the radio at 3.3V before switching tack and deciding to carry on using the ATmega to receive the data and to simply echo it out over the built-in UART. This ended up being so easy and still comparatively cheap.

[ The first time I tried this I ran the ATmega at 5V and used a 5V-3.3V level shifter – this worked great but also got really hot as I accidentally ended up powering the Pi from through the ATmega, which was being powered from an FTDI cable! ]

Yak Shave

I follow Dangerous Prototypes on Twitter and I was aware of Dirty PCBs. I bookmarked the site, waiting for the day when I actually had a need to get something bespoke made up by a board-house.

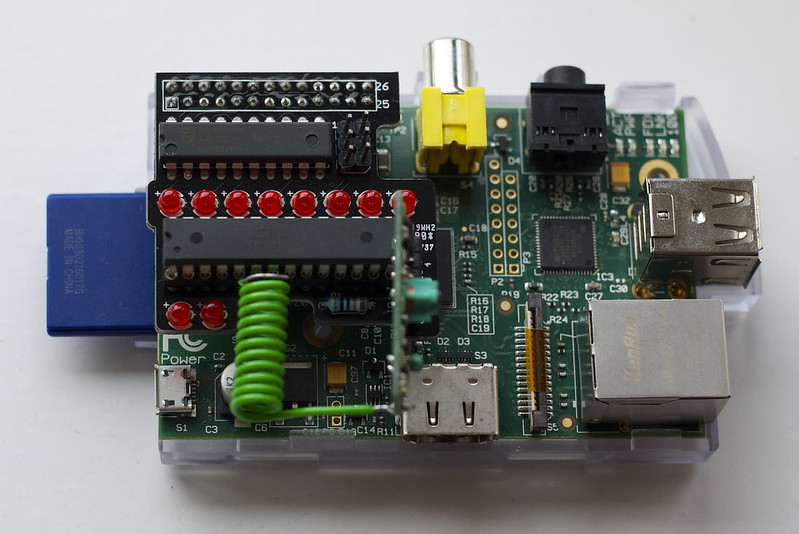

With a little success under my belt it seemed like a great time to distract myself with creating a board to tidy this all up. This Raspberry Pi “shield” is a great first PCB too: the space is small and this circuit was simple enough to be built with two layers and through-hole components.

I tried KiCad – I wanted to do this whole project with libre software, but I didn’t get on with KiCad (partially because I was using a Mac) and given the amount of new things I’d have to learn to produce a PCB anyway going down the Eagle route seemed the path of least resistence.

[ I may regret my choice of tool if I have to develop a larger board: the Eagle Light version that I used is limited to 10x8cm and 2 layers. It’s €140 for the hobbyist edition, which only gets you twice the area (though with 6 layers). The full version is just shy of €1000, and that’s without the autorouter. ]

Anyway, Eagle light was perfect. I followed this The Ben Heck Show video, which saved hours of reading documentation and I used the CAM files that Dirty PCBs provided which gave me the confidence that my Gerbers were probably going to be in the right format.

You can view the schematic here. All you need to know to read it is that Eagle will join things which have the same label (that is; all pins labelled “VCC” will get joined together when the board is routed).

8Mhz and 3.3V {#8mhz-and-33v}

The only noteworthy thing is that there are two voltage levels: I run the ATmega at 3.3V with the internal 8MHz oscillator, but the radio module gets 5V, which makes it run much more smoothly.

This works fine because the ATmega pins are 5V tolerant, but when running at 3.3V the output from the UART will be at levels compatible and safe to use with Raspberry Pi (which is a 3.3V device).

I used this baud rate guide to check that the internal oscillator would be stable enough to give me 9600 baud.

Normally Arduinos run at 16Mhz, with an external oscillator. This is actually how I wired up my ‘shrimp clone’ in the blog post above, but I could save three parts (two capactors and a crystal) by using the internal clock, and running at 16Mhz is unstable at 3.3V anyway.

Arduino IDE & Programming

I defined a new board for the Arduino IDE (which is done with .ini-style text files) with the fuses set how I want them and uploaded the bootloader for the Lilypad, which is also an 8Mhz device.

I used my trusty Bus Pirate to do all of the uploading, too, reusing an IDC10 cable to plug into the ICSP header (so I could plug and unplug the Bus Pirate without having to put all six wires back each time). I added a custom uploader to the Arduino IDE for this, too

Putting an ICSP header on my PCBs was an enormous time saver during the inevitable experimentation with bootloaders and fuses that was required.

(This is a third board, replete with super-bright SMT LEDs – my first SMT soldering, too. I desoldered these from a 12V halogen-replacement “bulb” that I damaged.)

Hardware Build

The boards arrived about a month later (squarely in the middle of the 1-8 weeks projected on the site) and all of the other parts that I needed had already turned up, so I built the first board the same day.

I put the octal latch and LEDs on first, because who doesn’t like a light-show?

Radio #1 First Run from Aaron Brady on Vimeo.

Once the almost foolproof part was proved working and I’d warmed up my iron, I soldered in a socket for the ATmega, the status lights, ICSP pins and a row of headers for the radio module.

I tested with a full Boarduino transmitting and with picocom receiving on the Pi-side: it worked!

Repurposing

Although this board was designed for the receiver, I only need one of those, and I have 10 boards. I’ve since repurposed one of the boards for a test transmitter:

(If I was doing this again, I would put unoccupied through-holes on the board, but this works fine.)

This test transmitter just echos the “hello” string over the radio. Adding a real analogue input and reworking the design to be lower power is probably going to justify a new board – but with this I can test how far away I can get from the transmitter before I get packet loss.

Conclusion

The schematic and Arduino code are available from the GitHub project page. DirtyPCBs.com is amazing. Chinese surface mail is slow (but cheap). If I can design a PCB, so can you.

(Oh yeah, and if you wanted … ten … of these you can buy them from DirtyPCBs)